Shimmer DeFi Education Session 2: Token Swaps - DEX vs. CEX

Session #2: Token Swaps — DEX vs. CEX

Presented by 0xHunter [15 September 2022]

Summary, organization and additional detail by DigitalSoul.x

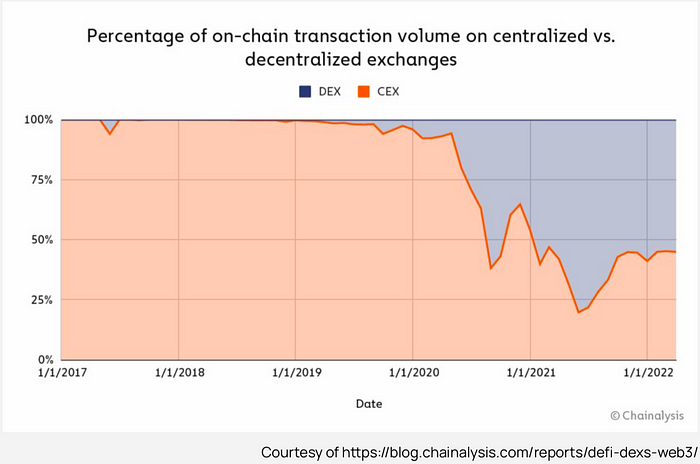

Welcome to the second Shimmer DeFi Education session of seven. In the first session, we explored the different types of cryptocurrency wallets and how to use them. This session deals with cryptocurrency exchanges: Centralized Exchanges (CEX) and Decentralized Exchanges (DEX). Both of these types of exchanges are online marketplaces for buying and selling cryptocurrencies. However, their modes of operation are very different and this session will consider the pros and cons of each.

Centralized Exchanges (CEX)

A centralized exchange is run by a corporation: Coinbase or Binance for example. They generally have features that appeal to new crypto investors such as convenient fiat on-ramps and off-ramps, polished user interfaces, customer service reps, etc. Because they have the backing of corporations, they have the appearance of being trustworthy and it’s true that they must conform to local regulations. But, since they are corporations they must also generate a profit and answer to their shareholders. Additionally, these CEX platforms act as a third party between traders and their coins. Many of them take custody of your coins while you are using the platform, and some of them might not even purchase the coins at all. They might simply generate an in-house ledger entry to account for your purchase without actually buying the coins in the first place.

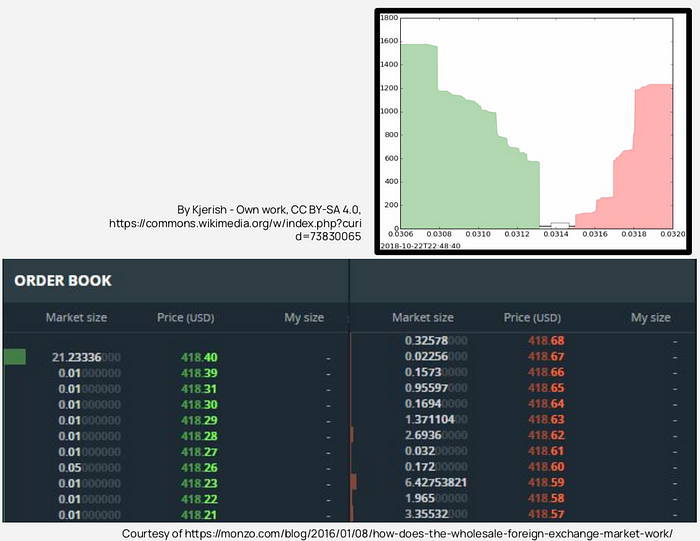

For trading, most CEX use the order book model. This is just a two-sided ledger of bids and asks (buys and sells). The difference between the bid and ask price is known as the spread. Trading on a CEX is generally through one of two methods: market orders and limit orders. When you place a market order, you are saying that you are willing to transact at whatever price your counterparty asks. If there is low liquidity for a particular coin, you may have to clear several orders to complete your transaction, and this will have an affect on the price. The advantage is that your order is filled immediately. Alternatively, when you place a limit order, you specify the price at which you wish to transact. Your order will remain open until there is a counterparty who agrees to transact at your price and then the trade happens automatically. While this gives you confidence in the price you will pay, there is a chance that it could take a long time for your order to get filled, if at all.

Strengths of CEX

- Deep Liquidity: Typically there are plenty of buyers and seller for assets on a CEX, so most orders can be completed quickly.

- Relationships with Established Market Players: CEXs may run promotions with established market players and in this case they might offer special perks to users.

- Strong Compliance with Local Regulations: As a corporation, a CEX must comply with local regulations in their area. This may help users to feel safe and comfortable since local regulations change often and can be difficult to keep up with.

- Enables Over-the-Counter Trading: You can structure deals in a very customized way using a CEX. Using a trusted intermediary offers some advantages when dealing with others or when placing orders for large amounts of cryptocurrency.

- Trading can be High Frequency: In many CEXs you can connect to APIs. This allows users to transact at a speed that is only limited by network latency, enabling actions that aren’t possible on a decentralized exchange.

Weaknesses of CEX

- Centralized: When an exchange is centralized, the leadership is generally localized in a certain area as well. They’re not only beholden to the local government, but to the CEO / shareholders of the company. They have an obligation to make a profit, and that profit usually comes from the fees that are passed on to their users. Also, their infrastructure is hosted on web2 platforms which are single points of failure.

- Custodial: Generally you don’t actually own your crypto assets when you deposit in an exchange. Instead, you own a legal IOU which is supported by the jurisdiction of the exchange. Because of this, you’re missing out on the core value proposition of blockchains: the ability to self-custody your own assets.

- Permissioned: Although it varies from one jurisdiction to the next, generally you will have to have to KYC to open a CEX account. You’re also at the mercy of their terms of service, and they can revoke your access at any time.

- Opaque Execution: While some exchanges do provide execution data about recent trades, at it’s core it’s still a web2 platform. At the end of the day you’re trusting the data that they host on their servers, and if you want to transact on their platform you must have faith that this information is accurate.

Decentralized Exchanges (DEX)

A decentralized exchange is also an online marketplace for buying and selling cryptocurrencies, but it is non-custodial. This means there is no need for a middleman and instead these peer-to-peer platforms are facilitated via smart contracts: code stored on a blockchain that perform certain functions when preset conditions are met. This allows for full transparency when trading.

Since there is no middleman, there is no entity in a DEX that can match buyers and sellers. This is in stark contrast to the order book model that a CEX uses. Instead, DEXs use a new facilitator called the liquidity provider. These participants ensure that there are tokens to be traded at all times by offering the different tokens in each aggregated liquidity pool: a group of two (or more) crypto assets managed by a smart contract. The simplest pools have balanced amounts of two different assets. If a liquidity provider wanted to enter a balanced pool of Ethereum and USDC for example, they would need to deposit 1 ETH (currently ~$1600) and 1600 USDC. By offering tokens to this pool, a liquidity provider is signaling that they’re always willing to trade ETH for USDC and vise versa. If the demand for ETH rises more quickly than that of USDC, the liquidity provider would then have less ETH in their position and more USDC. However, the total percentage of the pool represented by the liquidity provider’s position would remain unchanged.

In return for offering this service, liquidity providers receive rewards. One of the primary benefits of being a liquidity provider is that they collect a proportional amount of the fees of the trades made in the pool. When a token is first offered on a DEX there is generally a lot of volume. During this time it’s a great opportunity to provide liquidity and capture the fees, especially if relatively little liquidity has already been added to the pool. These fees can be added to your liquidity position, either automatically or manually depending on the protocol, adding to your position like compound interest. The fees may be offered in the form of one of the assets in the pool, or in the form of another token altogether known as a Liquidity Provider (LP) token. These LP tokens are platform-specific, but generally composable as well. In some cases you can deposit them with the protocol and receive a yield on them, a practice known as yield farming. You may also be able to borrow against them by using them as collateral. Different protocols have devised creative ways of adding value to these LP tokens.

The bottom line is that liquidity providers allow the DEX market to function by offering their tokens to traders. If there are very few liquidity providers, this will have a negative affect on a DEX. In this case, token holders that want to buy or sell won’t be able to without moving the price significantly during the course of the trade. Low liquidity increases volatility and doesn’t allow traders to get the maximum value for their tokens. Even after tokens are available for trading through the liquidity providing mechanism, there must still be a way to determine the price for each asset based on supply and demand. Enter the Automated Market Maker (AMM).

Automated Market Maker (AMM)

The Automated Market Maker (AMM) is simply a mathematical curve that determines the price of each asset in a pool based on the amount of each token in the pool:

Constant Product Automated Market Maker

The red curve illustrated above illustrates how the price of an asset reacts to changes in the amount of assets in a pool. Specifically, the prices of asset A and asset B are calculated via the formula x*y = k where ‘x’ is the amount of asset ‘A’, ‘y’ is the amount of asset ‘B’ and ‘k’ is a constant. For this reason, this type of AMM is called constant product. By way of example, let’s assume that a pool is balanced and the same amount of assets are available on each side. If a trader then comes in and continuously sells the same asset, the price asymptotically approaches zero but it never actually reaches zero. This ensures that there is always a price for each asset in the pool and tokens will be available for trading. Although liquidity is available at all times, it will decrease as the chart moves farther away from zero. Having assets available to trade as well as a price for each asset is extremely important to the operation of a DEX.

Small orders generally won’t result in a significant change in price if there is sufficient liquidity. However, larger orders can cause a significant change on the red line illustrated above. Slippage refers to the amount the price of an asset in a liquidity pool will deviate due to your trade. The higher the liquidity in a given pool, the less the slippage. Similarly, the lower the liquidity, the more the slippage. If you make a large trade, the price actually changes over the course of your trade. While this occurs in CEX order books as well, it’s a defined equation in a DEX. If there is not much liquidity and you wish to purchase a large amount of a given token, the slippage will be high and you will be paying more and more per token as your order gets filled.

To combat the effects of slippage, decentralized exchanges generally allow you to set a parameter called the slippage tolerance. This number represents the percentage price movement you’re willing to tolerate to execute the order. If you set the slippage tolerance to 1% for example, your order will only execute if the price moves less than or equal to one percent while executing your order. If your order would cause the price to move more than that, the DEX won’t be able to execute your order. This is important because it’s frequently difficult to know exactly how much the price will change as a result of your order since other traders can submit transactions to the same block. Most DEXs will inform traders of the expected slippage prior to executing an order.

Strengths of DEX

- Trustless: There’s no counterparty risk as you’re only interacting with smart contracts.

- Transparent: You can see all of the orders on the blockchain and you can verify the code executing the order if you like. The entire process is verifiable.

- Permissionless: There are no gatekeepers preventing access, enforcing terms of service or requiring KYC. Anyone in the world can participate.

- Composable: The DEX framework is modular and allows others to build on top of the foundations that exchanges have developed. In many cases this can even be done without the permission of the exchange. This allows for improved network effects in building different ecosystems.

Weaknesses of DEX

- Exploit Risk: The smart contract code could have a bug or an exploit leading to loss of funds. To minimize this risk, make sure that the smart contracts have been audited. For even more peace of mind, verify the audit at the website of the auditing company.

- Technical Complexity: Interacting with DEXs is fundamentally different and more complicated than interacting with CEXs. There is a learning curve involved and without a firm understanding of the basics, it can be easy to lose money. Some of the more subtle, advanced considerations will be explored in the next section.

Despite the exploit risk noted above, this can be mitigated by the Lindy Effect. This describes the belief that the longer a smart contract has been in use without being exploited, the more trustworthy it is. The amount of funds locked in these smart contracts tends to increase over time, making them more and more enticing to hackers. The more time has passed without exploit since the contract was put in use, the less the likelihood an exploit will be found. However, this is no guarantee, just a rule of thumb!

Advanced DEX Considerations

Impermanent Loss

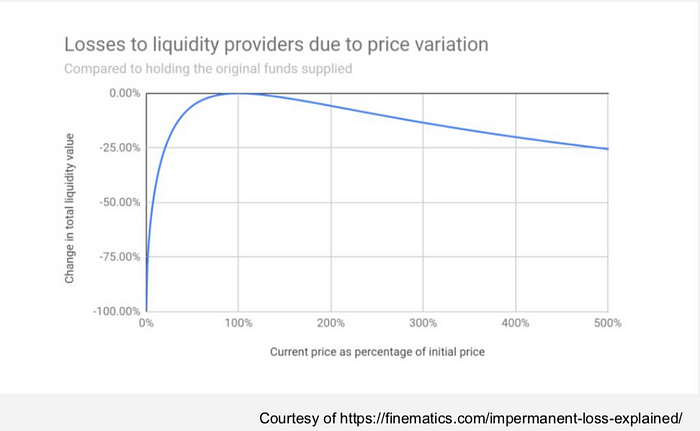

Impermanent loss describes the opportunity cost of being a liquidity provider compared to simply holding the two initial assets instead. It is a temporary loss of value that occurs as a result of changes in the price of the assets in the pool. Liquidity providers are always selling rising assets and buying falling assets by nature. In this way they are always on the wrong side of the profitable trade, but this doesn’t necessarily mean the trades are bad. There could be situations where an investor always wants their portfolio to be half ETH and half USDC. In that case, providing liquidity is essentially auto-rebalancing their portfolio. However, if their goal is to just make as much money as possible then it might have been more profitable to simply hold the assets without entering the pool.

The easiest way to illustrate impermanent loss is through example. First, assume that a liquidity provider has 1 ETH and 1000 USDT that are deposited into a liquidity pool on a DEX. At the time of the deposit, the price of ETH is $1000 and the price of USDT is $1. This means that the value of the deposit is $2000: $1000 for the ETH and $1000 for the USDT. Let’s also assume that this position represents 10% of the total constant product liquidity pool size. This tells us that the product ‘k’ for this pool is 100,000: 10 ETH * 10000 USDT.

Now, consider that the price of ETH goes up by a factor of 4 to $4000 while USDT remains the same. In the scenario, traders will use the pool to swap USDT for ETH until the ratio indicates the current price. Since the constant ‘k’ of 100,000 must be maintained in the pool, there would now be 5 ETH and 20000 USDT in the pool.

The liquidity provider is still entitled to their 10% of the pool. If they withdraw their assets from the pool at this point, they would receive 0.5 ETH and 2000 USDT. While their total value of assets has increased from $2000 to $4000 ($2000 in ETH plus $2000 in USDT), the value of the USDT portion of the deposit has decreased, resulting in an impermanent loss.

Note that if the liquidity provider had simply held the initial assets, the initial deposit of 1 ETH and 1000 USDT would now be worth $5000: $4000 for the ETH and $1000 for the USDT. The loss is called “impermanent” because it will only occur if the price of the assets in the pool changes while the liquidity provider has funds in the pool. If the prices of the assets return to their original values, or if the liquidity provider withdraws the funds before any significant price changes occur, they won’t experience any impermanent loss. Even so, the effects of impermanent loss can be offset by the trading fees. If there is sufficient volume in a certain price range over a long enough period of time, the fees generated by the protocol that are split among the liquidity providers can be more profitable than simply holding the initial assets.

It should be clear that providing liquidity is more complicated than most people believe. While there are services that attempt to aggregate and manage liquidity, it helps immensely to develop a strategy first. Providing liquidity should not be done passively unless the prices of the assets in the pool are tightly bound. Instead, liquidity providers should be more active to ensure that the asset prices don’t diverge too much. They should monitor their position to be able to remove liquidity when the assets prices reach the same ration that existed when the liquidity was first provided. Also, in some cases impermanent loss can be offset by yield farming: the practice of providing liquidity in order to earn rewards in the form of additional tokens or fees. Yield farming typically involves staking or locking up assets in a smart contract in exchange for the rewards, but can help to mitigate impermanent loss. However, these LP tokens can be highly volatile, so they are not without inherent risk themselves.

Miner Extractable Value (MEV)

MEV refers to value that can be extracted by actors based on the way a blockchain orders their transactions. On the Ethereum network, for example, there is an auction to order transactions. There’s even an ‘MEV Searcher’ community that bids to get certain transactions included in each block to extract the value. This is considered a negative example of MEV, since miners can essentially choose the transactions with the highest extractable value to include in a given block. By contrast, the Shimmer network has unordered transactions so some of the MEV opportunities are mitigated.

Another example of MEV is arbitrage: buying an underpriced asset from one exchange and selling it for more on another. This is generally considered positive because it equalizes prices across markets. It also limits fragmented liquidity and promotes healthy markets. On the Ethereum network this generally happens in the same block. Even on platforms where the transactions are not orderable, arbitrage still exists. Instead, it’s just in sequential blocks. When transactions can be ordered, traders will want to submit theirs as quickly as possible to front-run other traders. This happens in real-time, leading to virtually zero lag time between price equalization on decentralized exchanges. In this way arbitrage is generally viewed as positive for DeFi.

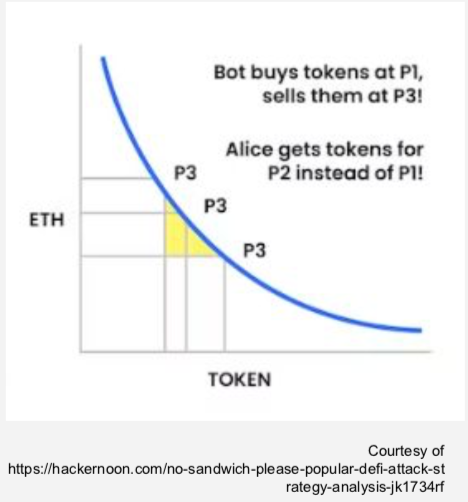

The last example of MEV to discuss is related to the slippage tolerance we discussed earlier. If a trader notices there is an order waiting to be filled and that person will tolerate one percent slippage, the trader can go in and buy the asset up to the maximum price that the other will tolerate. Then, immediately after the other person buys it for the one percent higher price that they set, the trader will sell the asset for the profit. This is generally considered predatory and doesn’t add value, but it’s also not profitable to do this to very small trades due to gas fees. It’s also only a problem on Ethereum and other blockchains where you can order transactions.

Alternate AMM Models

In the example we viewed above, we considered the simple constant product AMM popularized by Uniswap. However, instead of using the x*y=k curve, a protocol could implement any curve they want. In fact, many protocols are still experimenting with different curves for different models. Stated otherwise: “The curve is the protocol.”

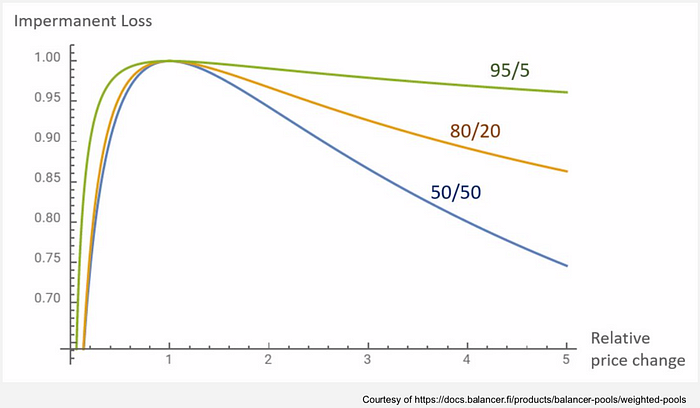

Also, we considered pools that were balanced 50%-50% but this can be adjusted as well. Perhaps one pool is 95% ETH and 5% USDC. One of the consequences of changing the weight of the pool is that the liquidity providers are less exposed to impermanent loss. Also, if a token is newly launching but the project doesn’t have matching value in another token to start the pool, they could provide 80% of the position in their token and 20% in a stablecoin, for instance. The trade-off is that there’s more slippage and potentially higher fees for traders due to the imbalanced liquidity.

Also in the initial AMM model we discussed, there were only two assets in the pool. Actually there could be many more assets in a given pool. Offering exposure to several different assets can provide interesting opportunities to liquidity providers. Curve is one protocol that is well-known for multi-asset pools. For instance, there might be a pool that is comprised of three different stablecoins. As a liquidity provider, you’ll get the volume for all three of those stablecoins trading against each other. Also, the prices of each of these coins are more tightly bound together because they’re priced in terms of one another. If there is sufficient liquidity, one of the tokens can always be traded for another. However, if one of the stablecoins is risky compared to the others and that one depegs, then your liquidity position is in jeopardy. In this case, traders will quickly come in to arbitrage and buy the two good stablecoins. In the end, these multi-asset pools expose each asset to the others, making these pools more risky.

It gets really interesting if you combine several of these factors. For example, maybe there is a weighted, multi-asset pool similar to one offered by Balancer. This could be a liquidity position tailored to a specific portfolio. In this case, you can be sure that the asset allocation you desire for the portfolio is maintained while you are collecting the fees generated by trading in the pool.

In conclusion, while DEXs are much more complicated than CEXs, the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks and allow for privacy and self-custody — key features of cryptocurrencies. At the same time, CEXs do have their place and can provide peace of mind regarding regulations as well as convenient fiat on- and off-ramps.